## Rebounds from 2023 NBA Season

rebounds <- c(260, 114, 252, 310, 165, 236, 148, 336, 941, 127, 384, 278, 300, 6, 136, 145, 233, 142, 420, 35, 11, 161, 485, 1, 830, 81, 112, 16, 63, 513, 162, 296, 434, 239, 22, 269, 235, 222, 485, 245, 578, 162, 281, 344, 39, 99, 82, 79, 476, 3, 69, 84, 201, 52, 223, 244, 34, 728, 5, 423, 286, 346, 324, 549, 580, 152, 401, 58, 95, 187, 618, 189, 69, 184, 34, 101, 36, 7, 472, 78, 41, 631, 259, 12, 760, 33, 410, 672, 70, 227, 272, 247, 289, 63, 96, 500, 497, 739, 188, 178, 491, 1, 298, 202, 211, 307, 227, 439, 253, 24, 740, 168, 921, 61, 210, 213, 209, 150, 145, 220, 26, 144, 286, 190, 56, 182, 580, 105, 402, 660, 260, 118, 0, 231, 11, 184, 69, 432, 807, 257, 762, 24, 42, 342, 95, 185, 77, 310, 170, 447, 98, 271, 8, 41, 99, 85, 102, 593, 275, 24, 10, 206, 407, 51, 184, 0, 98, 10, 305, 43, 112, 30, 80, 312, 292, 292, 899, 182, 317, 511, 665, 78, 633, 314, 32, 11, 49, 205, 402, 296, 46, 26, 261, 429, 451, 66, 546, 206, 35, 5, 63, 161, 227, 394, 308, 118, 92, 249, 691, 257, 85, 220, 483, 233, 909, 744, 564, 208, 573, 25, 243, 16, 2, 30, 132, 34, 468, 460, 330, 268, 1, 252, 318, 453, 473, 33, 82, 494, 26, 450, 54, 110, 145, 870, 670, 111, 1, 179, 448, 700, 74, 845, 30, 27, 639, 15, 97, 705, 96, 54, 295, 312, 556, 39, 551, 426, 45, 258, 8, 233, 564, 630, 536, 5, 255, 95, 173, 11, 51, 106, 71, 393, 317, 149, 394, 301, 319, 19, 147, 257, 336, 350, 19, 416, 829, 2, 219, 1530, 171, 124, 54, 47, 296, 30, 26, 96, 168, 14, 118, 770, 310, 66, 934, 42, 415, 204, 634, 202, 301, 391, 177, 81, 256, 116, 188, 76, 417, 1, 28, 435, 191, 449, 270, 265, 5, 1, 0, 47, 183, 0, 22, 247, 0, 381, 19, 2, 862, 253, 469, 55, 37, 90, 246, 78, 88, 512, 0, 101, 265, 28, 238, 223, 257, 372, 21, 236, 94, 81, 295, 206, 704, 454, 607, 145, 129, 282, 405, 247, 1258, 15, 269, 9, 240, 260, 305, 75)3 Vectors

So far, we have dealth with scalar numbers and texts. But, when working with data, we will observe many units and need a way to store all their values together. This is where the bread and butter of data-science comes in: Vectors.

Vectors are a list of elements like integers, numbers, or strings. This is really useful for storing data! You use c to create a vector (pneumonically, c stands for combine).

It is kind of a pain in the neck to write all these out; and worse, prone to errors! Later, we will learn how to load data from a file, making this much easier.

You can access elements of a vector by using [#], where # is the \(i\)-th element you want

rebounds[1][1] 260rebounds[2][1] 114If you want to access more than one element, we can subset using a vector! (how meta):

rebounds[c(1, 2)][1] 260 114One special syntax is ther a:b which generates \(a, a+1, \dots, b\). This makes it easy to grab the first 5 values:

rebounds[1:5][1] 260 114 252 310 165Standard math operators work on vectors element by element:

rebounds[1:5] + 1[1] 261 115 253 311 166rebounds[1:5] / 12 # dozens of rebounds[1] 21.66667 9.50000 21.00000 25.83333 13.75000If we want to know how many elements are in a vector, we can use the length function:

length(rebounds)[1] 3863.1 Summarizing vectors

The natural next step is to start trying to summarize the data. There are a set of built-in functions that provide statistical summaries of the data.

## Mean, standard deviation, and variance

mean(rebounds)[1] 250.4663sd(rebounds)[1] 232.6362var(rebounds)[1] 54119.62## Extremes

max(rebounds)[1] 1530min(rebounds)[1] 0## chaining functions

sqrt(var(rebounds))[1] 232.6362Some functions will take extra arguments that give more instructions. For example, the quantile function returns information about percentiles of the distribution. You can add extra arguments, separated by commas. For example, quantile’s first argument is a vector and the second argument is what percentiles you want to find.

## Percentiles of the data

quantile(rebounds, c(0.1, 0.5, 0.9)) 10% 50% 90%

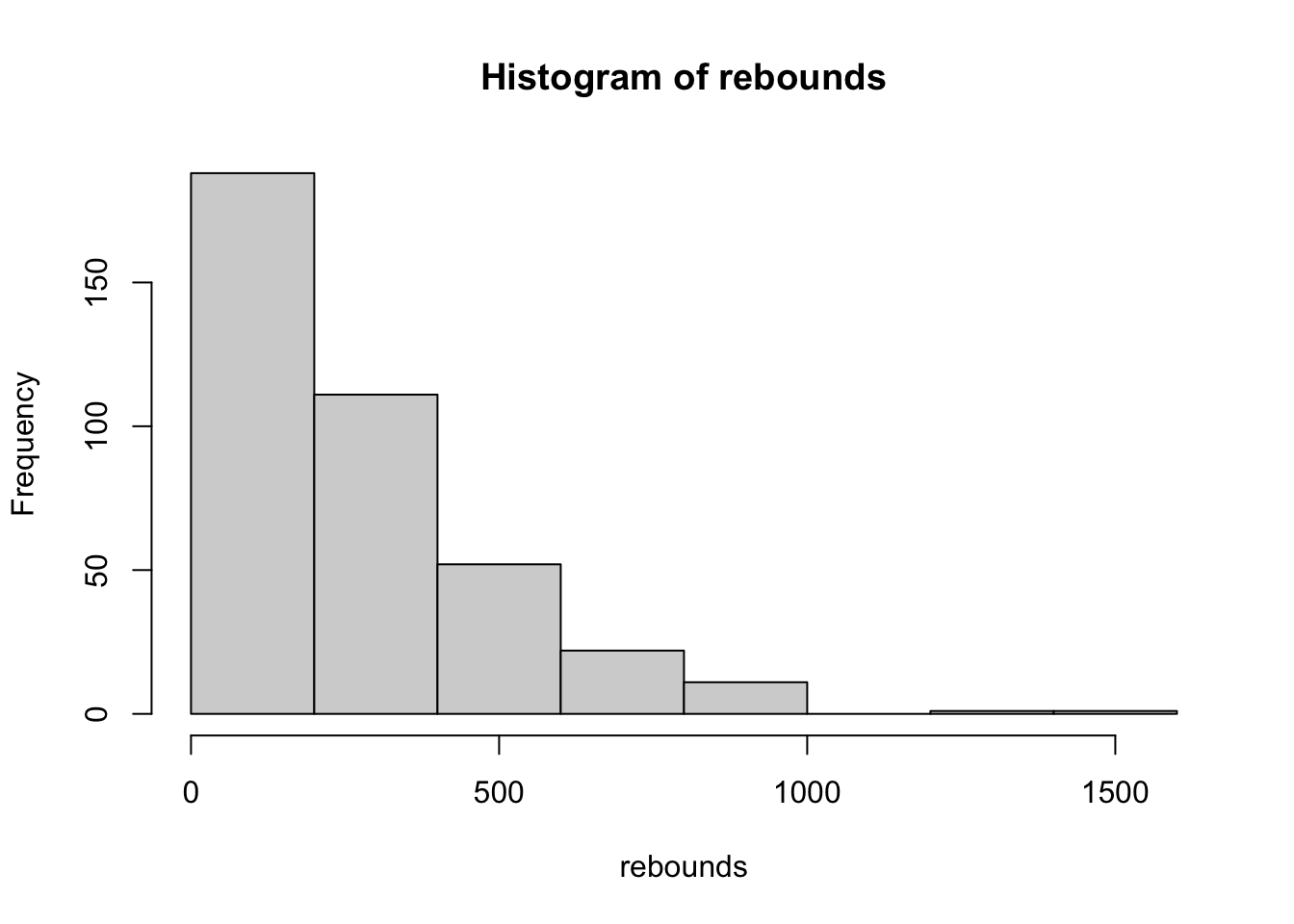

19.0 205.5 575.5 We will talk in more details about plotting below, but for now we can use the hist() function to give us a view of the distribution of the vector

hist(rebounds)

3.1.2 NAs

In the real world, some times we will not have a value for a variable for an individual (e.g. people don’t fill answer a survey question). In R, this is represented as an NA.

reviews <- c(5, NA, 4, 4, 3, 5, NA, 4, 5, 2)What is the average (mean and median) review?

mean(reviews)[1] NAmedian(reviews)[1] NABy default, the statistical summary functions will all produce NA when they are present in the data. R wants you to opt-in to ignoring the missings. To do this, functions will take an extra argument called na.rm:

mean(reviews, na.rm = FALSE)[1] NAmax(reviews, na.rm = FALSE)[1] NAA lot of this information will be presented to you by the summary function. For numberic vectors, summary produces the five-number summary, the mean, and the number of NAs (if any)

summary(reviews) Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max. NA's

2.00 3.75 4.00 4.00 5.00 5.00 2 3.1.3 Logical Vectors

So far, we have seen two kinds of vectors: numeric and character vectors. A third, common, vector is a logical vector:

ordered_takeout <- c(TRUE, TRUE, FALSE, TRUE, FALSE, TRUE, FALSE, FALSE)Logical vectors can take only two values: TRUE and FALSE. They can be treated as numbers by using as.numeric() with TRUE becoming 1 and FALSE becoming 0.

as.numeric(ordered_takeout)[1] 1 1 0 1 0 1 0 0One common trick is to use sum() on a logical vector and it will return the number of TRUEs:

sum(ordered_takeout)[1] 4Logical vectors are often returned by other operations. For example, we can check whether elements of a vector equal some value with ==. Other operators that produce a logical vector include >, <, >=, and <=.

## Find five-star reviews

reviews == 5 [1] TRUE NA FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE NA FALSE TRUE FALSE## Find three-star or lower

reviews <= 3 [1] FALSE NA FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE NA FALSE FALSE TRUELogical vectors can be negated using the ! operator:

## Find non five-star reviews

!(reviews == 5) [1] FALSE NA TRUE TRUE TRUE FALSE NA TRUE FALSE TRUEYou can also use the following operators to supply multiple criteria:

&And operator. Both vector 1 and vector 2 must be true for the observation|Or operator. Either vector 1 or vector 2 must be true for the observation

(reviews == 5) & (reviews == 4) [1] FALSE NA FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE NA FALSE FALSE FALSE(reviews == 5) | (reviews == 4) [1] TRUE NA TRUE TRUE FALSE TRUE NA TRUE TRUE FALSE## Equivalent to

reviews >= 4 [1] TRUE NA TRUE TRUE FALSE TRUE NA TRUE TRUE FALSE3.1.4 Subsetting of vectors by logical

We have already discussed one way of subsetting vectors via a vector of integers. This is called “subsetting by index”.

The other common way is by using a logical vector the same length of the vector you wish to subset. For example, let’s look at the reviews for takeout orders and dine-in orders separately

## Takeout orders

reviews[ordered_takeout][1] 5 NA 4 5 5 2## Dine-in orders

reviews[!ordered_takeout][1] 4 3 NA 43.1.4.1 Exercise

- What is the average review for take-out orders?

- The

is.na()function takes a vector as an argument and returns a logical vector that equalsTRUEif the element isNA. Using this and the!, subset the reviews to only non-NAvalues. What is the average review? Comapre this tomean(reviews, na.rm = TRUE).

mean(reviews[!is.na(reviews)])[1] 4mean(reviews, na.rm = TRUE)[1] 43.1.5 Vectorized operations

Often times we want to use multiple vectors for some calculation. Like single numbers, arithmetic can be done element-by-element with vectors. This means +, -, *, / and ^ all work on a vector.

x <- c(1, 2, 3)

y <- c(5, 5, 5)

x + y[1] 6 7 8x^2[1] 1 4 9There are two main features to remember: 1. The vectors you use should be of the same length (if they are not, some weird recycling rules occur that we will not discuss in this introduction). 2. Scalars are treated as a vector of the same length with that single number repeated for each element.

## Equivalent:

x + 2[1] 3 4 5x + rep(2, 3)[1] 3 4 5More, many functions are designed to be used on vectors element by element. All of the functions we used in the “Calculator” section do this:

exp(x)[1] 2.718282 7.389056 20.085537log(x)[1] 0.0000000 0.6931472 1.0986123sqrt(x^2)[1] 1 2 33.1.5.1 Exercise

- Try to guess the output of the following expression

2*x + y + 1.

3.1.6 Sorting data

The final vector operation we will discuss is how to sort data; either ascending or descending in value. There are two ways to do this.

First, we can use the sort() function. The function takes a function and an optional decreasing argument. decreasing takes a logical TRUE/FALSE option. By default, it increases in values

sort(rebounds, decreasing = TRUE) [1] 1530 1258 941 934 921 909 899 870 862 845 830 829 807 770 762

[16] 760 744 740 739 728 705 704 700 691 672 670 665 660 639 634

[31] 633 631 630 618 607 593 580 580 578 573 564 564 556 551 549

[46] 546 536 513 512 511 500 497 494 491 485 485 483 476 473 472

[61] 469 468 460 454 453 451 450 449 448 447 439 435 434 432 429

[76] 426 423 420 417 416 415 410 407 405 402 402 401 394 394 393

[91] 391 384 381 372 350 346 344 342 336 336 330 324 319 318 317

[106] 317 314 312 312 310 310 310 308 307 305 305 301 301 300 298

[121] 296 296 296 295 295 292 292 289 286 286 282 281 278 275 272

[136] 271 270 269 269 268 265 265 261 260 260 260 259 258 257 257

[151] 257 257 256 255 253 253 252 252 249 247 247 247 246 245 244

[166] 243 240 239 238 236 236 235 233 233 233 231 227 227 227 223

[181] 223 222 220 220 219 213 211 210 209 208 206 206 206 205 204

[196] 202 202 201 191 190 189 188 188 187 185 184 184 184 183 182

[211] 182 179 178 177 173 171 170 168 168 165 162 162 161 161 152

[226] 150 149 148 147 145 145 145 145 144 142 136 132 129 127 124

[241] 118 118 118 116 114 112 112 111 110 106 105 102 101 101 99

[256] 99 98 98 97 96 96 96 95 95 95 94 92 90 88 85

[271] 85 84 82 82 81 81 81 80 79 78 78 78 77 76 75

[286] 74 71 70 69 69 69 66 66 63 63 63 61 58 56 55

[301] 54 54 54 52 51 51 49 47 47 46 45 43 42 42 41

[316] 41 39 39 37 36 35 35 34 34 34 33 33 32 30 30

[331] 30 30 28 28 27 26 26 26 26 25 24 24 24 22 22

[346] 21 19 19 19 16 16 15 15 14 12 11 11 11 11 10

[361] 10 9 8 8 7 6 5 5 5 5 3 2 2 2 1

[376] 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0Alternatively, we can use the order() function to get the row indices of the ordering:

order(rebounds, decreasing = TRUE) [1] 298 379 9 313 113 215 177 244 347 252 25 295 139 310 141 85 216 111

[19] 98 58 258 371 250 209 88 245 181 130 255 317 183 82 272 71 373 158

[37] 65 127 41 219 217 271 263 265 64 197 273 30 356 180 96 97 238 101

[55] 23 39 213 49 235 79 349 227 228 372 234 195 240 332 249 150 108 330

[73] 33 138 194 266 60 19 327 294 315 87 163 377 129 189 67 204 285 282

[91] 320 11 344 364 292 62 44 144 8 291 229 63 287 233 179 283 184 174

[109] 262 4 148 311 205 106 169 385 286 319 13 103 32 190 303 261 369 175

[127] 176 93 61 123 376 43 12 159 91 152 333 36 381 230 334 359 193 1

[145] 131 384 83 268 140 210 290 363 323 275 109 348 3 232 208 92 342 378

[163] 353 40 56 221 383 34 361 6 366 37 17 214 270 134 90 107 203 55

[181] 362 38 120 212 297 116 105 115 117 218 162 198 370 188 316 104 318 53

[199] 331 124 72 99 325 70 146 74 136 165 339 126 178 248 100 321 277 299

[217] 149 112 307 5 31 42 22 202 66 118 284 7 289 16 119 243 374 122

[235] 18 15 225 375 10 300 132 206 309 324 2 27 171 246 242 280 128 157

[253] 76 358 46 155 151 167 257 95 259 306 69 145 276 367 207 352 355 156

[271] 211 52 47 237 26 322 368 173 48 80 182 354 147 326 386 251 281 89

[289] 51 73 137 196 312 29 94 201 114 68 125 350 241 260 301 54 164 279

[307] 187 302 338 191 267 170 143 314 81 154 45 264 351 77 20 199 57 75

[325] 226 86 236 185 172 224 253 304 329 360 254 121 192 239 305 220 110 142

[343] 160 35 341 365 288 293 345 28 222 256 380 308 84 21 135 186 278 161

[361] 168 382 153 269 78 14 59 200 274 335 50 223 296 346 24 102 231 247

[379] 328 336 133 166 337 340 343 357The first element of the resulting vector is the index of the maximum number (1530)

order(rebounds, decreasing = TRUE)[1][1] 298which.max(rebounds)[1] 298What this means is that we can use the result of order to subset the vector to get the sorted vector:

rebounds[order(rebounds, decreasing = TRUE)] [1] 1530 1258 941 934 921 909 899 870 862 845 830 829 807 770 762

[16] 760 744 740 739 728 705 704 700 691 672 670 665 660 639 634

[31] 633 631 630 618 607 593 580 580 578 573 564 564 556 551 549

[46] 546 536 513 512 511 500 497 494 491 485 485 483 476 473 472

[61] 469 468 460 454 453 451 450 449 448 447 439 435 434 432 429

[76] 426 423 420 417 416 415 410 407 405 402 402 401 394 394 393

[91] 391 384 381 372 350 346 344 342 336 336 330 324 319 318 317

[106] 317 314 312 312 310 310 310 308 307 305 305 301 301 300 298

[121] 296 296 296 295 295 292 292 289 286 286 282 281 278 275 272

[136] 271 270 269 269 268 265 265 261 260 260 260 259 258 257 257

[151] 257 257 256 255 253 253 252 252 249 247 247 247 246 245 244

[166] 243 240 239 238 236 236 235 233 233 233 231 227 227 227 223

[181] 223 222 220 220 219 213 211 210 209 208 206 206 206 205 204

[196] 202 202 201 191 190 189 188 188 187 185 184 184 184 183 182

[211] 182 179 178 177 173 171 170 168 168 165 162 162 161 161 152

[226] 150 149 148 147 145 145 145 145 144 142 136 132 129 127 124

[241] 118 118 118 116 114 112 112 111 110 106 105 102 101 101 99

[256] 99 98 98 97 96 96 96 95 95 95 94 92 90 88 85

[271] 85 84 82 82 81 81 81 80 79 78 78 78 77 76 75

[286] 74 71 70 69 69 69 66 66 63 63 63 61 58 56 55

[301] 54 54 54 52 51 51 49 47 47 46 45 43 42 42 41

[316] 41 39 39 37 36 35 35 34 34 34 33 33 32 30 30

[331] 30 30 28 28 27 26 26 26 26 25 24 24 24 22 22

[346] 21 19 19 19 16 16 15 15 14 12 11 11 11 11 10

[361] 10 9 8 8 7 6 5 5 5 5 3 2 2 2 1

[376] 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0This might seem like a bit silly, but it will prove useful when we want to sort multiple vectors at the same time based on one of the vectors.

3.1.6.1 Exercise

- Create a vector with the following 20 observations and call it

height:

64, 65, 64, 66, 67, 64, 67, 66, 66, 67, 70, 66, 70, 68, 68, 67, 69, 67, 67, 69

Use

lengthand confirm there are twenty observationsSubset the first 4 elements of the

heightSubset the last two elements of

height. Do not hardcode 20, instead calculate it withlength()Compute the five-number summary, the mean, and the sd of

height.Print out the heights in order from tallest to shortest